Georg (69) looks back on his years in coal in the town of Lauchhammer — a time when hard work meant good money. Today, he views the energy transition with a critical eye.

“I moved to Lauchhammer in 1961 because my father got a job here, at the Lauchhammer Brown Coal Combine. After finishing school, I went to the army — one and a half years of military service. In between, I’d already been working in coal — as a labourer, during the holidays. I earned money — good money. Coal always paid about a third more than the average wage in the rest of the country.

I actually studied automation engineering, but they needed people in high-voltage engineering, so I ended up in the combine’s energy supply department. That’s where I worked right up until the fall of the Wall –as an energy supplier and in open-cast mining.

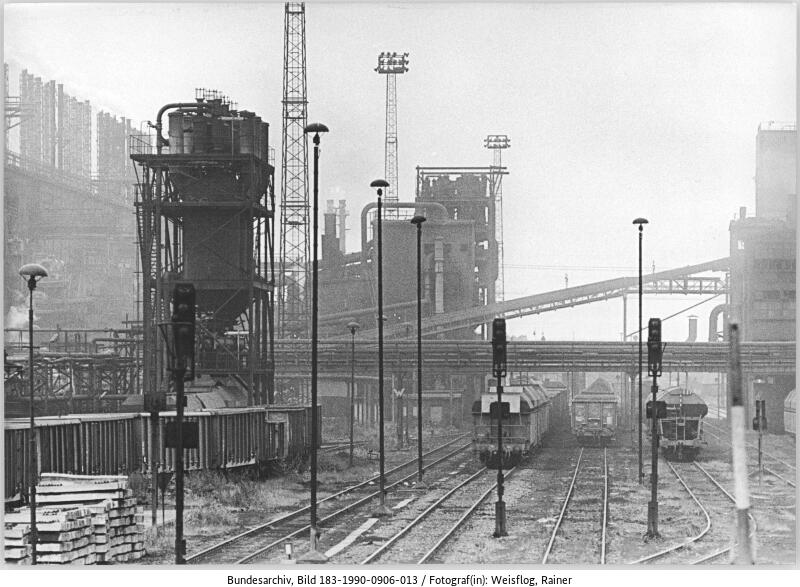

For anyone who doesn’t know: everything that rolls, hisses, pumps, or moves in any way needs energy — and a lot of it. Brown coal was basically the only major energy source we had in the GDR. The Cottbus energy district, and especially the Lauchhammer Brown Coal Combine, were always pioneers in that field.

You could say, yes, we really developed socialism properly. But as an energy supplier, you had one job — no matter what system you were in: ensuring a reliable supply. That was the be-all and end-all. Three hundred and sixty-five days a year, around the clock. Holidays didn’t matter. Vacations had to be planned carefully, there were three-shift systems — and it all worked. Until 1990, when the Wall came down, as many had long hoped. Only, no one really knew what would come next or what it would look like.

There was a real dilemma here, especially in a place so dependent on one industry like Lauchhammer. We had coal mining, coal processing, all the way to the big Lauchhammer coking plant. Then on the other side, there was TAKRAF Lauchhammer — the machinery manufacturer that built the huge excavators and conveyor bridges for the open-cast mines — and alongside that, the art foundry.

After reunification, a lot collapsed — the entire state-owned industry. The Treuhand, as we all know, completely failed in its mission. It was actually founded in the GDR to privatise public property, but then our West German partners took it over entirely and basically dismantled everything East German — just like they did in so many other areas. Because, well, the East Germans got in the way somehow.

Now, almost thirty years later, we’re facing another kind of transformation — this time in energy. The idea is to move away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy — light, air, sun, hydropower, and so on. At the moment, though, it’s in a very unsatisfactory stage. We still need fossil energy to be available — for example, when the lights suddenly go out, or at night, when the sun doesn’t shine for eight or twelve hours. And if there’s a “dark lull” — no wind, no sun — then fossil fuels have to step in to keep the energy supply stable across Germany. That’s hitting the big power plants and the remaining open-cast mines here particularly hard.

And there are still major cuts to come. Even the so-called “coal pennies” — the billions meant to create new jobs here — won’t really solve it. It’s not working properly for the people, for the former workers in the coal and energy industries who had hoped for more. The whole process needs to be handled much better by the people sent here from Berlin and Potsdam — the ones who are supposed to create new jobs.

Personally, I left coal after 1990 — I didn’t let myself get pushed out. We already knew back then that coal wasn’t the big deal anymore, if you looked at the millions of tonnes mined in the last years of the GDR. We ourselves helped make coal less necessary — with heating conversions in old GDR buildings, and the closure of factories that no longer needed energy. It was clear to us something had to change. So we told each other: find work as soon as you can. Ideally, work where you can still look at yourself in the mirror and say, yes, I’ve done something worthwhile — at least for a while. I was only 35 then.

So I looked for something new — in finance. That’s where I got a look behind the scenes: how the Deutschmark worked, how the market worked. I saw good things — but also a lot of bad ones. Big scams, big promises made the night before or the afternoon before, and the next morning no one remembered a thing. Mostly it was people sent from European or West German banks who’d moved in here. To put it bluntly: there were plenty of examples of how the East was ruthlessly taken for a ride. Profit was all that mattered. The people — the former workers — didn’t matter at all. They just threw a cloak over everything: ‘We’ll set up employment schemes, qualification programmes. Come on, we’ll train you for two, three, four years, and then you can get back into the regular job market.’ And I wanted to look behind that.

When I realised that in this new sector there was a lot of bluffing, covering up, and polishing going on, I quit. That was the reason — not because anyone fired me. After about ten years, I resigned voluntarily, after the banks told us we’d have to take responsibility for their mistakes — as small brokers, small financiers. I didn’t want to be part of that anymore. A lot of others didn’t either. They called it ‘going to zero’ — transferring your working hours down to zero, and then goodbye without severance pay. I didn’t get a single penny of compensation. I settled it with myself.”